AUDIT OUTCOMES

In the third year of the current administration, we continue to see improvement in the audit outcomes in national and provincial government.

None

Status of 2020-21 audits

In this chapter, we share the audit outcomes of departments and public entities and reflect on the drivers of these outcomes. Where relevant, we also reflect on the improvement trend, its sustainability and the overall areas to which leadership and oversight must direct attention. We do not deal in detail with the impact and causes of these outcomes, except where some examples are provided – chapters 3 to 9 delve deeper into these matters, and our recommendations are reflected in chapter 10.

This chapter is broken down into the following sections:

- An overall reflection on the status of our 2020-21 audits

- The trends in the overall audit outcomes

- The status of financial management, with particular focus on the quality of the financial statements and the financial health of departments and public entities

- The quality of the reporting on the performance of auditees

- Auditees’ compliance with legislation, with a specific focus on supply chain management legislation

- The irregular expenditure resulting from non-compliance, and how auditees dealt with it

- The overall root causes of the less-than-ideal audit outcomes

The covid-19 pandemic continued to affect our audit processes and resources, as the finance minister extended the submission dates for the 2019-20 financial statements for auditing, which affected the period in which we could audit. As a result, we were auditing local government in early 2021, when we would normally have started with the department and public entity audits. This late start, together with the challenges of auditing during a pandemic (including our staff falling ill), delayed the finalisation of some of the audit reports.

By 15 October 2021 (the cut-off date for including the audit outcomes in this report), there were still 42 audits (10%) outstanding. Of these, 23 were outstanding because auditees had either not yet submitted their financial statements for auditing or had submitted them late. We include more information on this in the section on financial statements, and also tell the story of some of the prominent auditees at which the audits have not been finalised.

By the time this report is tabled, some of the remaining audits will have been finalised. Chapter 1 includes all the audit outcomes as of the tabling date.

The improvement in audit outcomes that we reported last year continued, with 48 auditees (11%) seeing a net improvement over the three years of the current administration.

This trend is evident at both departments and public entities, although departments generally have better audit outcomes.

The 113 auditees (47 departments and 66 public entities) with a clean audit status represent 19% of the R1,9 trillion expenditure budget managed by national and provincial government.

The number of clean audits increases every year due to significant effort and commitment by the leadership, officials and governance structures of these auditees.

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (EC)

Audit outcomes improved due to leadership’s commitment to attaining clean audit outcomes.

The department strengthened its record keeping, which was the root cause of the previous year’s findings on the performance report, and established processes to validate the reported performance information before it was reviewed by internal audit and the audit committee. This enabled the department to support the current year’s reported performance information with the required evidence.

NTP Radioisotopes

In the previous year, the entity had an unqualified opinion, with one compliance finding relating to its strategic planning and approval processes.

The accounting authority and senior management implemented our recommendation on the required approval processes, as well as proper process and monitoring controls to ensure compliance with all legislative strategic planning requirements.

It is often difficult for an auditee to sustain a clean audit if it does not have effective financial and performance management systems and controls. It is commendable that 61 auditees (54%) have managed to retain their clean audit status since the first year of the current administration.

Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation

The department managed to sustain its clean audit outcome because of its mature internal control environment. Importantly, critical preventative controls are continuously reviewed to ensure that they remain relevant (in line with the latest laws, regulations and industry best practice) and effective.

In addition, all assurance providers are committed to fulfilling their monitoring, governance and oversight roles. We noted that the department takes all audit findings seriously, regardless of whether they are classified as ‘other important’ or ‘administrative matters’. It makes a concerted effort to resolve findings as soon as they are raised to prevent them from reoccurring or escalating in the next audit cycle.

Dube TradePort (KZN)

The entity sustained its clean audit status by institutionalising and monitoring key controls, remaining committed to accountability, and having its board and governance structures provide assurance. Stability at executive and middle- to senior- management level also contributed to a strong control environment. A tone of clean administration has been entrenched within the entity at all levels, and it has strong internal controls for record management, reviews, reporting processes and continuous compliance monitoring for all key legislation that forms part of its mandate. The entity uses its internal audit services to allow for a robust assessment of the internal control activities. Financial statements are prepared twice yearly and reviewed by the audit committee, while internal audit performs a detailed review of the annual financial statements and performance report.

Some of the common practices that enabled auditees to sustain their clean audit status include institutionalising and monitoring key controls (including preventative controls), and having all assurance providers, including management and leadership, commit to fulfilling their monitoring, governance and oversight roles. The auditees must continue to apply these best practices if they are to sustain these favourable audit outcomes, otherwise the outcomes may regress.

Department of Community Safety (GP)

The department, which achieved a clean audit in 2019-20, regressed in 2020-21 due to material findings on the quality of the performance report. The findings reflect inadequate controls and processes to ensure that the reported performance is reliable and that the regulations for managing performance information are followed to ensure indicators and targets are verifiable. The regression is attributed to the lack of effective and proper record management processes.

Armaments Corporation (Armscor)

The entity regressed from a clean audit status in the previous year due to a lack of internal controls for in-year and year-end reporting. Its financial systems are fragmented and require manual interventions, which increases the risk of misstatements in its financial statements. The process to collate and consolidate information from different financial systems was also extremely time-consuming, adding to the time constraints for adequate reviews. As a result, we reported a non-compliance finding on the quality of the financial statements the entity submitted for auditing.

There are 31 auditees that are very close to obtaining a clean audit status, and only need to address one finding on the quality of their annual financial statements (24 auditees), performance against predetermined objectives (one auditee) or compliance with procurement legislation (six auditees). Some of these auditees have been working towards this goal for many years and we encourage them to do what it takes to overcome the last hurdles. If they do, we expect to see an increase in the number of clean audits for 2021-22.

Department of Economic Development and Tourism (MP)

The department has been making steady progress towards a clean audit outcome, as evident from the reduction of material compliance findings from four in the previous year to only one in the current year. The remaining finding relates to a material misstatement in the submitted financial statements. This admirable improvement is due to management’s commitment to institutionalise controls and deal with findings from the previous year’s audit. If this trend continues in the 2021-22 financial year, the department will achieve a clean audit outcome.

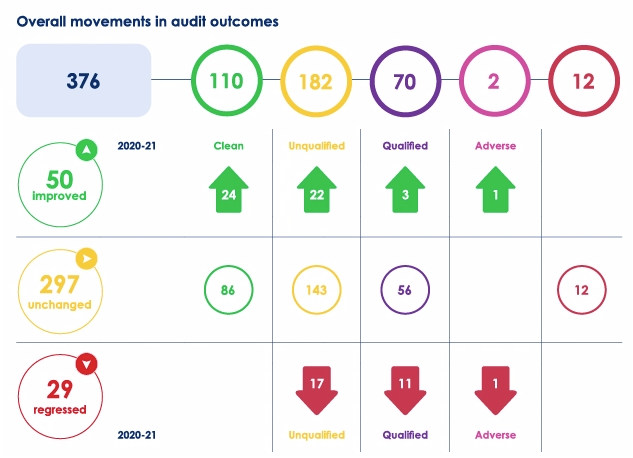

Movement of audit outcomes

The figure below shows the change in audit outcomes for the 376 auditees we audited in the previous year. It excludes the seven new auditees that we audited for the first time in the current year, three of which received clean audits while four were financially unqualified with findings.

Auditees that received a financially unqualified opinion on their financial statements but still had material findings on the quality of their performance reports and compliance with key legislation account for 46% of the expenditure budget.

Of these auditees, 107 have been in this category since the first year of the current administration.

We encourage auditees to apply the same vigour to these two important areas as they do to upgrading financial reporting, as being complacent on these areas creates a culture of tolerance for poor performance and for transgressions, affecting the auditee’s ability to fully focus on its mandate of service delivery to citizens. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, some of these auditees have worked hard on the remaining challenges over the past few years and are now close to attaining a clean audit.

Key service delivery departments and state-owned enterprises

In our previous general reports, we have consistently highlighted the need to pay specific attention to the key service delivery departments and state-owned enterprises, commonly referred to as SOEs, because they have the greatest impact on the service delivery needs of the citizen and the financial health of government. Their audit outcomes are a good indicator of their ability to fully discharge their mandate.

The audit outcomes for the key service delivery departments within the health, education, human settlements and public works sectors are worse than those of other departments. Only two of these departments (provincial departments of health, and of transport and public works in the Western Cape) obtained a clean audit status and many of the departments that struggle to produce credible financial statements are in these sectors. These departments also lag behind other departments in the improvement trend. We unpack the problems experienced in the sectors and the impact they have on service delivery in chapter 4.

While the audit outcomes of public entities show a definite upward trend, this is not evident for SOEs. Many of the SOE audits are outstanding because their financial statements were not submitted for auditing (as detailed later in this chapter), and the outcomes where the audits were completed are dismal. We provide more detail and insights on the troubling state of affairs at SOEs in chapter 6.

Financial management

Accounting officers and authorities managed an estimated expenditure budget of R1,9 trillion in 2020-21(including outstanding audits).

At a time when departments and public entities need to do more with less, and the public’s demands for service delivery and accountability are increasing, accounting officers and authorities should do everything in their power to get the most value from every rand spent and to manage every aspect of their finances with diligence and care.

In this section, we highlight our concerns about the current state of financial management by looking at auditees’ financial statements and financial health. We also demonstrate why this is an important discipline, as it directly affects the decisions made to better serve our citizens.

Quality of financial statements

Credible financial statements are crucial for enabling accountability and transparency, but many auditees are failing in this area.

Auditees are required by legislation to submit their financial statements on time. The goal of this requirement is to ensure that auditees account for their financial affairs when this information is still relevant to stakeholders for decision-making and oversight. Most of the 10% of auditees that did not submit their financial statements on time were public entities, with only one department (the Western Cape Department of Education)

submitting late.

Why are the financial statements important?

Financial statements are an important tool that provide an account of an auditee’s financial affairs. They show how the auditee spends its money, where its revenue comes from, its assets and the state of those assets, how much it owes creditors, how much it is owed by its debtors, and whether the money owed is expected to be received. The financial statements also give insight into an entity’s committed financial obligations and whether the entity will be able to honour these commitments when they fall due.

In addition, the financial statements provide crucial information on how the auditee adhered to its budget; the unauthorised, irregular, and fruitless and wasteful expenditure it incurred; and its overall financial position – in other words, whether its operations are financially sustainable.

The financial statements are used by the committees in Parliament and the legislatures to hold accounting officers and authorities to account and to make decisions on, for example, the allocation of the budget. For some public entities, creditors, banks and rating agencies also use the financial statements to determine the level of risk in lending money to the entity. In addition, members of the public can use the financial statements to see how well the auditee is using the taxes they pay to provide services.

If we audit and express an unqualified audit opinion on the financial statements, it means that there were no material misstatements (errors or omissions) in the financial statements and the users of those financial statements can trust the credibility of the information.

The following table shows the 17 public entities that had not submitted their financial statements by 15 October 2021. Most of these public entities are SOEs, and we provide more information on the delays in chapter 6.

Over half of auditees continue to submit poor-quality financial statements for auditing, although

some of them corrected all of the misstatements we identified. Had this not been the case, only 47% of auditees with completed audits would have received unqualified audit opinions, compared to the 78% that ultimately received this outcome.

Auditees have inadequate controls to prevent misstatements in their financial statements. This results in misstatements not being detected through the various levels of review, including reviews by the chief financial officer internal audit and the audit committee, before the financial statements are approved by the accounting officer or authority. Auditors are then under pressure to identify the misstatements as part of the audit process so that the auditees can make the corrections needed to obtain an unqualified audit opinion – a practice that is neither efficient nor sustainable.

Over the years, this reliance on audit teams to identify misstatements in the financial statements has placed undue pressure on the audit teams to meet the legislated deadlines for completing the audits, as well as the unintended consequence of increased audit costs.

The poorly prepared financial statements and significant activity to make corrections in response to the audit means that leadership makes financial decisions throughout the year based on financial information that is not credible. The treasuries and oversight bodies (such as portfolio committees) also use in-year reporting for monitoring purposes, and without reliable information, their monitoring process is ineffective. As detailed later in this chapter, auditees’ poor monitoring and corrective action throughout the year is one of the main reasons for the concerning financial health status of departments and public entities, which threatens their ability to provide much-needed services to citizens.

In total, 22% of auditees with completed audits could not correct all of the material misstatements

we identified during our audit, and received qualified, adverse or disclaimed audit opinions (collectively called ‘modified audit opinions’). This is a slight improvement from the 25% in the previous year, but a solid improvement from the 30% in the first year of administration.

Outside the audit process, auditees must improve the quality of their financial statements and focus on the identified root causes of modified opinions.

The Pan South African Language Board improved from a qualified opinion to an unqualified opinion. The public entity was qualified on its disclosure of property, plant and equipment in 2019-20, but was able to reverse the qualification by strengthening its preventative internal controls and action plans. During the financial year, the entity appointed a chief financial officer who assisted in implementing controls around the asset register. The chief financial officer established a task team to perform monthly asset reconciliation, identified assets which were not depreciated, investigated the reasons for not depreciating the assets as required by the applicable standard and where necessary, depreciated these assets retrospectively. Audit action plans were tracked at chief financial officer and audit committee level. There was also stability amongst those charged with governance, including the board and the audit and risk committee.

Gateway Airport Authority Limpopo regressed from a qualified opinion to an adverse opinion. In the 2019-20 financial statements we identified material misstatements in a number of areas, none of which were addressed in the 2020-21 financial year. We also identified further material misstatements in other financial statement items.

The regression was caused by breakdown in the public entity’s financial reporting checks and balances, a collapse of governance structures, and instability in leadership. The position of chief financial officer was vacant for the entire financial year and the official appointed to act in the position was suspended and later dismissed. The chief executive officer was also suspended and an official who was seconded to act in the position passed away during the initial stages of the audit. The public entity also did not have an internal audit unit, audit committee or accounting authority – all of which have important assurance responsibilities in the financial reporting chain.

A qualified audit opinion means that there were areas in the financial statements that we found to be materially misstated (material errors or omissions that are so significant that they affect the credibility and reliability of the financial statements). In our audit reports, we point out which areas of the financial statements cannot be trusted. In total, 70 auditees (31 departments and 39 public entities) received qualified audit opinions.

Adverse and disclaimed audit opinions

Adverse and disclaimed audit opinions are the worst opinions an auditee can receive. An adverse opinion means that the financial statements included so many material misstatements that we disagree with virtually all the amounts and disclosures. A disclaimed opinion means those auditees could not provide us with evidence for most of the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. Effectively, the information in financial statements with adverse or disclaimed opinions can be discarded because it is not credible. In our audit reports, we tell oversight structures and other users of the financial statements that the information cannot be trusted. In 2020-21, Gateway Airport Authority (LP) and Ehlanzeni TVET College received adverse opinions.

Over the years, we have called on national and provincial leadership and oversight to direct their efforts towards auditees that continue to receive disclaimed opinions. In 2020-21, 12 public entities received disclaimed opinions. All 12 public entities had also received disclaimed opinions in 2019-20.No department received a disclaimed audit opinion during this period.

Below, we share the stories of four public entities with disclaimed opinions or that have a history of such opinions but had not yet submitted financial statements for auditing at the cut-off date for this report. These examples are intended to demonstrate that a disclaimed audit opinion not only reflects poor financial reporting, but often indicates a collapse of the auditee’s control environment, which also affects its ability to deliver on its mandate and manage its finances.

Free State Development Corporation

The Free State Development Corporation earns revenue by leasing the commercial and residential properties it owns, and charging interest on the loans it offers to small, medium and micro enterprises as part of its primary mandate. The entity does not receive significant grants, as it is meant to be financially self-sustaining.

In 2020-21, the entity received its second consecutive disclaimed opinion because it could not confirm its ability to continue operating. To improve its cash flow, recover its long-outstanding debt (96% of which has been deemed irrecoverable) and ensure its survival, the entity needs to recover all rental and utilities from its tenants. However, it outsourced billing and collecting these amounts to a service provider. In terms of the agreement with the service provider, all amounts collected from tenants were to be paid over to the entity. However, the service provider has since gone into voluntary liquidation and owes the entity R109,2 million for amounts collected from tenants that had not been paid over. In the previous year, the service provider only paid over R4,8 million of the R37,5 million collected, resulting in a material irregularity and a likely financial loss of R32,7 million.

The entity has experienced instability in the board, which was disbanded in June 2021, as well as uncertainty and instability in the chief executive officer position. Without a board, the entity cannot improve its financial position. Due to its dire financial situation, the entity did not have the funds to deliver on its primary mandate.

The member of the executive council for Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs must prioritise appointing a competent board, developing and executing a turnaround strategy, and filling key vacancies to address the entity’s financial viability challenges. The entity should also use its in-house legal department to recover the long-outstanding debts owed by tenants instead of paying external parties to do so.

Compensation Fund

The Compensation Fund’s primary objective, and core activity, is compensating workers for disablement caused by injuries and diseases sustained in the course of their work and for death resulting from such injuries or diseases. All employers are required by law to register with the fund.

The fund generates its revenue from levies paid by employers. In 2019-20, this amounted to R12,5 billion, while total benefits paid, as included in the 2019-20 financial statements, were R6,6 billion.

For the past eight years, the fund has received a disclaimed audit opinion because it could not provide credible and accurate financial and performance information for auditing.

We have repeatedly highlighted the pervasive weaknesses in the fund’s control environment, including lack of reconciliations, inadequate review of underlying records, lack of record keeping and non-compliance with legislation. Furthermore, short-term solutions, such as using consultants, have not been effective, and fund leadership has not developed mechanisms to respond to the identified weaknesses.

The fund has struggled to process claims and medical invoices from service providers because claims are not adequately reconciled against supporting documentation. Some service providers exploited this deficiency by submitting and receiving payments for duplicate claims, while others took the fund to court, where it was ordered to pay the outstanding invoices with interest, causing further losses.

Due to deficiencies in the fund’s information technology systems, some employees were able to collude with medical service providers and individuals outside the organisation to process fraudulent transactions. The fund has also failed to effectively implement consequence management processes or recover the money lost.

The 2020-21 audit is still ongoing, but we have already notified the accounting authority of two material irregularities relating to overpayments made to a medical service provider and interest paid due to late payment of medical invoices.

While the fund has introduced a new information technology system to facilitate claims and address the previous system’s shortcomings, the full benefits have yet

to be seen.

To improve its audit outcome, the fund must implement our previous recommendations:

- to urgently review its control environment, including the role of management, and then strengthen preventative and monitoring controls to identify deficiencies early and react appropriately

- to strengthen its performance and consequence management processes to ensure that officials are fully accountable for their duties

- to urgently finalise investigations and implement recommendations based on the outcomes of these investigations

- to appropriately address the two identified material irregularities.

Independent Development Trust

The Independent Development Trust is responsible for delivering social infrastructure and social development programme management services on behalf of government. The current year’s audit was still in progress at the cut-off date for this report because the entity submitted its financial statements late.

The entity obtained disclaimed audit outcomes in five of the last six financial years. In 2018-19, it received a qualified audit outcome after re-evaluating and correcting some of the matters that had resulted in previous negative audit outcomes, but this improvement was not sustainable.

The executive authority, being the minister of public works and infrastructure, is responsible for appointing a board of trustees that serves as the accounting authority, in line with the provisions of the entity’s trust deed.

However, from 2017-18 until August 2021, the entity did not have a properly constituted board of trustees to make major decisions on its strategic direction. It also experienced a leadership and oversight vacuum due to vacant senior management positions and instability in the positions of chief executive officer and chief financial officer.

Adding to these challenges were an ongoing organisational development process, uncertainty about the entity’s future and a moratorium on filling vacancies, which led to staff shortages and low staff morale.

This resulted in inadequate preventative controls over daily and monthly processing and reconciliation of transactions, poor record keeping, and severe deficiencies in the entity’s information technology environment.

The Special Investigating Unit also has three ongoing investigations at the entity, relating to procurement management and possible unlawful, improper or irregular conduct. During the 2019-20 audit, we also detected project-related irregular expenditure of R54,95 million.

This hampered the entity’s ability to execute its mandate, especially as it relates to delivering infrastructure projects. As a result, fewer departments requested its services as implementing agent on projects to deliver critical services, and management fee revenue steadily declined from R227 million in 2015-16 to R149 million in 2019-20. Going concern issues ensued and the entity now relies on bailouts from the Department of Public Works to continue operating.

We are hopeful about recent developments, such as the appointment of a properly constituted board of trustees and the statement by the public works and infrastructure minister that proposals on the entity’s future should be approved by the end of 2021.

To improve its financial and performance management, become financially viable and, ultimately, deliver on its mandate, the entity needs a clear financial and business recovery plan, and must prioritise its human resources and information technology systems. Staff at all levels should also support the implementation and monitoring of key preventative internal controls.

Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa

The Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (Prasa) is responsible for delivering rail-commuter services and long-haul passenger rail and bus services within, to and from the country on behalf of government.

The entity received a disclaimed opinion in both 2018-19 and 2019-20, partly due to property, plant and equipment. In response, it embarked on an extensive asset verification process, which delayed the submission of financial statements and thus our audit. The other disclaimed areas were unspent conditional grants, revenue from non-exchange transactions, prior period errors, commitments, risk management, irregular and fruitless and wasteful expenditure, and other comparative misstatements.

The reasons that Prasa cannot improve its audit outcome include its poor control environment and the ineffective implementation of an audit action plan – partly because of instability in key leadership positions due to vacancies and prolonged employee suspensions. Compounding this are shortcomings in the entity’s governance, risk management and internal control processes caused by instability at board and executive management level, as well as an internal audit unit and audit committee that are not fully effective.

Prasa’s poor control environment as reported on in our audit reports as well as its failing infrastructure and resultant unreliable service, ongoing delays and frequent accidents, have all contributed to the decline in the entity’s achievement of its strategic objectives from 55% in 2016-17 to 17,5% in 2019-20, and 25% in 2020-21*.

In addition, the entity did not effectively spend its capital grants, which negatively affected the timely maintenance and replacement of its core assets and resulted in train delays, non-functioning rail corridors and generally unreliable service. These service-offering challenges contributed to a gradual decline in fare revenue from R1,6 billion in 2016-17 to R69,8 million in 2020-21*, adding to its financial challenges.

Over the last four years, Prasa has remained one of the largest contributors to irregular expenditure (mostly caused by non-compliance with supply chain management regulations), and fruitless and wasteful expenditure (mainly because no value was derived from payments made). In 2020-21*, the balance of the entity’s irregular expenditure stood at R29,3 billion and fruitless and wasteful expenditure stood at R467 million. As these balances have largely not been investigated, no consequences are being implemented against those responsible.

We also identified nine material irregularities at the entity.

The cumulative impact of these weaknesses has been both substantial and negative, and has affected the entity’s operations and service offering to rail commuters who rely on this affordable transport service, as well as the South African economy as a whole. Adding to these woes are protracted and delayed supply chain management processes. This is evident in the rolling stock fleet renewal programme, which is supposed to enable a more reliable train service but is not delivering fast enough, and in the lack of infrastructure development to modernise depots and stations.

The minister’s appointment of the board during 2020-21 and the filling of the group chief executive officer and group chief financial officer positions is a step in the right direction. To further turn Prasa’s situation around and improve service delivery to citizens, the entity should prioritise:

- enhancing oversight, governance and accountability by the newly appointed board and executive management team to strengthen the control environment and address the causes of poor audit outcomes

- filling the remaining executive management positions with appropriately skilled and experienced personnel

- developing and implementing audit action plans, with a focus on root causes, to address audit findings and improve audit outcomes

- monitoring performance and consequence management, especially around supply chain and contract management

- implementing disciplined financial reporting processes, underpinned by solid accounting and financial management knowledge

- improving asset management by maintaining and/or replacing core assets, and instituting adequate and effective security measures to protect such assets.

* Unaudited reported figures for 2020-21

Financial health

Our audits included a high-level analysis of financial health indicators for departments and public entities. The goal is to give management of these entities an overview of selected aspects of their current financial management and enable corrective action to be taken as soon as possible if the auditees’ operations and service delivery may be at risk. We also performed audit procedures to assess whether there were any events or conditions that might cast significant doubt on an auditee’s ability to continue its operations in the near future.

Based on this analysis, we determined the extent of unfavourable indicators and gave each auditee an overall assessment as follows:

The unfavourable indicators are shared later in this chapter. We normally conclude overall that an auditee’s financial health is concerning if there are multiple indicators of financial strain, such as a deficit, and inability to pay creditors and/or paying them late, an inability to recover debt, or dipping into the next year’s budget to cover the current year’s expenses.

If we look at the financial health of auditees in proportion to the expenditure budget for which they are responsible, we can see that there is pressure on the finances of the auditees responsible for the bulk of the budget. Only 30% of the budget is managed by auditees with good financial health.

The auditees at which intervention is required include the following:

- Fourteen auditees responsible for 1% of the budget received adverse (two auditees) or disclaimed (12 auditees) opinions on their financial statements, which means that the financial statements were not reliable enough to analyse.

- Thirty-two auditees responsible for 11% of the budget disclosed in their financial statements that, based on the state of their finances, there is significant doubt that they will be able to continue with their operations in future. These auditees often need to scale down their operations and obtain financing or even bailouts to keep operating.

Auditees responsible for 58% of the budget were not yet in a position where they would not be able to continue operating, but there are indicators that this might soon be the case.

Departments responsible for 8% of the budget disclosed in their financial statements that they were in a particularly vulnerable position at the end of the financial year and that they might be at an operational risk in the future.

The status of unauthorised expenditure also provides a view of departments’ financial health and shows where they have overspent their budgets.

Unauthorised expenditure occurs when departments:

- used more funds than had been allocated (in other words, overspending)

- used allocated funds for purposes other than those intended.

Unauthorised expenditure for 2019-20 included R15,13 billion incurred by the Department of Social Development from paying the April 2020 social grants early in response to the covid-19 lockdown measures. If we exclude this anomaly, the unauthorised expenditure in 2019-20 would have been R2,99 billion. These figures indicate that unauthorised expenditure has increased every year since 2018-19, although the number of departments that incurred such expenditure decreased in 2020 21.

The unauthorised expenditure was mostly caused by departments overspending their budgets. Budget cuts and reprioritisation, along with emergency spending in response to the covid-19 pandemic, meant that departments had reduced funding available to fully cover their operational costs. Claims against the state further reduced available budgets (as detailed later in this section).

Departments from the Eastern Cape, the Free State and the Northern Cape were the main contributors to such expenditure, making up 87% of the total as follows:

- Eastern Cape – R2,05 billion (64%)

- Free State – R0,48 billion (15%)

- Northern Cape – R0,26 billion (8%)

The provincial health and education departments alone incurred R2,83 billion in unauthorised expenditure. We discuss the concerning financial state of these sectors in chapter 4.

The Eastern Cape departments of Education and Health, the Free State Department of Police, Roads and

Transport, and the North West Department of Health have incurred unauthorised expenditure for the past three years, including overspending on their key service delivery programmes, mainly on employee compensation:

- Department of Education (EC) – public ordinary school education programme

- Department of Police, Roads and Transport (FS) – administration (R0,04 billion) and transport regulations (R0,07 billion) programmes

- Department of Health (NW) – public district health services programme

In the case of the Eastern Cape Department of Health, unauthorised expenditure was due to medico-legal claims.

Before we provide further details on the key indicators we used to analyse the financial health of departments, it is important to understand how the financial analysis of departments is different from that of other auditees and private-sector entities.

Departments prepare their financial statements on what is called the modified cash basis of accounting. The amounts disclosed in the financial statements are only what was actually paid during the year and do not include accruals (the liabilities for unpaid expenses) at year-end. While this is common for government accounting, it does not give a complete view of a department’s year-end financial position.

We believe it is important for management to understand the state of their departments’ finances, which may not be easily seen in their financial statements. This is why, every year, we reconstruct the financial statements at year-end to take these unpaid liabilities into account. This allows us to assess and report to management whether the surpluses they reported are the true state of affairs and whether they have technically been using the following year’s budget because of over commitments in a particular year.

The key indicators analysed below exclude auditees with adverse and disclaimed audit opinions.

The sustainability indicators and the high unauthorised expenditure paint a picture of departments unable to operate within their budgets, resulting in deficits, cash shortfalls and bank overdrafts.

The main contributors to the R41,74 billion deficit

in departments were:

- Department of Public Enterprises – R21,57 billion (52%)

- Department of Health (GP) – R4,47 billion (11%)

- Department of Education (EC) – R2,90 billion (7%)

Over 60% of departments had insufficient funds to settle all liabilities that existed at year-end – in other words, they had cash shortfalls. This means that these departments started the 2020-21 financial year with part of their budget effectively pre-spent.

The consolidated cash shortfall of the 27 departments (18%) that had already spent more than 10% of their 2021-22 operating budget (excluding employee costs and transfers) amounted to R31,08 billion, with the highest percentage incurred by:

- Department of Social Development (national) – 3 637% (cash shortfall = R15 228,11 million, following year’s operating budget =

R418,70 million) - Office of the Premier (FS) – 311% (cash shortfall = R188,72 million, following year’s operating budget = R60,63 million)

- Department of Public Works (KZN) – 285% (cash shortfall = R776,07 million, following year’s operating budget = R272,16 million)

At the national Department of Social Development, the shortfall occurred when the president announced the lockdown in March 2020 and a decision was made to pay some of the April 2020 grants in March. This resulted in the R15 billion overpayment in grants for the 2019-20 financial year as well as a bank overdraft. This shortfall has not been funded from the 2020-21 allocation and will need a resolution from the Standing Committee on Public Accounts to regularise the unauthorised expenditure.

The KwaZulu-Natal Department of Public Works uses an overdraft facility that was approved by the provincial treasury to procure on behalf of other client departments, and its cash reserves are thus always negative. The client departments are taking a long time to repay some of their outstanding debts, which is also a contributing factor.

We also continued to see an increase in litigation and claims against departments, which we have flagged as an emerging risk since the previous administration.

Before getting into the analysis, let’s first take a look at what this involves.

Claims are made against departments through litigation for compensation as a result of a loss caused by the department – the most common being medical negligence claims against provincial health departments.

Departments do not budget for such claims, which means that all successful claims will be paid from funds earmarked for service delivery, further eroding their ability to be financially sustainable and to deliver on their service delivery commitments.

The estimated settlement value of the claims against the state totalled R166,07 billion at the 2020-21 year-end.

This amount represents the claims made against the state that have not yet been settled (by court order or mutually between the parties). In accordance with the reporting department reports an estimated value based on the most likely outcome of the process. As in the previous year, the provincial health departments accounted for the largest portion of this amount at 75%.

Over a third of the departments had claims against them with an estimated settlement value that exceeded 10% of their following year’s budget. If paid out in 2021 22, this would use up more than 10% of these departments’ budgets meant for other strategic priorities, including service delivery.

Chapter 4 of this report includes more details on claims in the health and education sectors, as well as their impact. Outside of these sectors, the following departments have the highest claims:

- Department of Police – R7,71 billion, mostly in relation to wrongful arrests, unlawful or unnecessary use of firearms/shooting, collisions or damages to vehicles/properties, and assaults during arrest or interrogation.

- Department of Defence – R5,51 billion , mostly in relation to to an old case regarding a commission claim that is being defended in the Civil Court of Lisbon, Portugal, with a rand value of R3,3 billion. The department is opposing the claim. Other claims include a proposed settlement of R305 million instituted by a sub-contractor of Denel against the department, as well as various claims for breach of contract, loss of income, collisions, unlawful arrest, damages, unpaid invoices, etc. to the value of R1,8 billion.

- Department of Higher Education and Training – R5,16 billion, R5 billion of which relates to a case lodged jointly against the National Student Financial Aid Scheme and the minister of higher education and training, which relates to intellectual property infringement. The department is a second respondent on the claim.

- Department of Justice and Constitutional Development – R2,98 billion, mostly in relation to legal services rendered by the Office of the State Attorney on behalf of client departments.

If the departments do not pay the claims to beneficiaries by the court-ordered date, they must also pay interest, which causes further financial loss.

The key source of revenue for departments is the budget they receive from government. Some departments also generate revenue, which they need to collect to have enough cash to operate. Any surpluses at year-end are paid back into the National Revenue Fund or into provincial revenue funds, which then fund departments’ budgets in the following year. Departments continued to struggle to collect the debt owed to them, as indicated by long debt-collection periods and the significant portion of debt that is deemed irrecoverable. Failing to collect debt affects not only the operation of the specific department, but also the funds available for future government initiatives.

Almost all departments had unpaid expenses (accruals) at year-end, totalling R28,58 billion. Although the average time it takes departments to pay their creditors is edging closer to the required 30 days, a third of departments cannot pay their creditors on time. This affects the cash flow of the suppliers with which government is doing business and stands in sharp contrast to the objectives of stimulating the economy and especially supporting the small, medium and micro enterprise sector. For example, contractors working on infrastructure projects stop their work until they receive payment, which causes significant delays, as detailed in chapter 6. The interest charged on late payments is also a financial loss that departments can ill afford.

Although delayed payments are typically due to poor controls and processes, other contributing factors include the financial difficulty experienced by some departments, as well as the lack of cash to honour their obligations (as described earlier in

this section).

We now turn to the financial state of public entities (excluding SOEs), including constitutional institutions, government business enterprises, trading entities, public entities that are not profit-driven, and the technical and vocational education and training (TVET) colleges. Many of these entities are instrumental in achieving service delivery targets in areas such as infrastructure development, economic development and skills development. The entities also include those delivering services to the public and regulators that protect the public.

Overall, there has been a slight improvement at these public entities, with more entities improving their financial health status than regressing.

The deficit of R7,58 billion was incurred by 61 public entities with expenditure that exceeded their revenue. Of this, 45% was incurred by schedule 3A public entities that are funded through revenue such as levies and taxes and that will need additional funding. The public entity with the highest deficit in the past few years was the Road Accident Fund, but the audit of the fund had not been completed by 15 October and thus the information is not included in this report.

The major contributors to the R7,58 billion deficit were:

- Roads Agency Limpopo – R1,20 billion (16%)

- Gautrain Management Agency – R1,01 billion (13%)

- Agricultural Land Holding Account – R0,67 billion (9%)

- Freedom Park Trust – R0,47 billion (6%)

- Health and Welfare Sector Education and Training Authority – R0,43 billion (6%)

In total, 23 public entities were in a net current liability position, meaning that they had more short-term debt than assets such as cash and debtors.

The public entities in the most difficult position were the 13 that owed more money at year-end than they had in the bank, with the top three being:

- Corridor Mining Resources (LP) – 16 088% (creditors = R18,22 million, cash available = R113 244)

- North West Parks Board – 1 370% (creditors = R36,89 million, cash available = R2,69 million)

- Central Medical Trading Account (FS) – 935% (creditors = R323,59 million, cash available = R34,62 million)

The inability to pay creditors on time is another indicator of pressure in the finances of these public entities and, as mentioned earlier in this section, has a negative impact on their suppliers. Late payments are more common at public entities than departments, and the entities took an average of 70 days to pay their creditors. The public entities that took the longest to pay their creditors were:

- Traditional Levies and Trust Account (KZN) – 561 days

- Capricorn TVET College – 493 days

- Elangeni TVET College – 482 days

To pay creditors, public entities need revenue, but over half of these entities had more than 10% of their debt that was not recoverable.

The figure below shows the public entities whose financial health is of greatest concern, based on the disclosure in their financial statements that there is significant doubt that they will be able to continue their operations.

In addition to those public entities that obtained disclaimed audit opinions, the following public entities received modified audit opinions because of significant doubt that they will able to continue their operations:

- Free State Development Corporation

- Golden Leopard Resorts (NW)

- GL Resorts (subsidiary of Golden Leopard Resorts) (NW)

Even though most public entities would be able to continue their operations, the negative indicators raise concerns about the financial viability of some of these entities, and about the pressure to acquire additional funding from government in the form of government grants transferred from either national or provincial departments.

Below are examples of some of the reasons why these entities were able to continue operating.

The South African National Roads Agency was able to continue operating by shifting funds from the non-toll portfolio to the toll portfolio, refinancing maturing debts and postponing capital projects in the toll portfolio.

Great North Transport is a schedule 3D public entity, and is thus required to be self-sustaining. However, for the past five years it has received grant allocations from the Limpopo Department of Economic Development,

Environment and Tourism, as well as financial rescues from the provincial treasury to help it recapitalise and reduce the amount owed to creditors.

Entities such as Corridor Mining Resources, Golden Leopard Resorts and GL Resorts were able to operate because they received loans or financial support from parent or holding companies.

The South African Civil Aviation Authority reduced its operating expenses and limited capital expenditure to only critical projects. It also received R155 million in additional funding from the Department of Transport for 2020-21.

Fruitless and wasteful expenditure is expenditure that was made in vain and that could have been avoided if reasonable care had been taken.

Government cannot afford to lose money because of poor decision-making, neglect or inefficiencies, making the extent of fruitless and wasteful expenditure a good indicator of how the public purse is being managed.

The reduction in fruitless and wasteful expenditure from the previous year is encouraging, but losing just over R1,7 billion that could have been used for the pressing service delivery needs of citizens is a red flag for government and needs urgent attention. A total of 36% (R0,62 billion) of this expenditure was interest and penalties – this means auditees paid their creditors late and even paid over tax to the South African Revenue Service late because of their poor financial position.

A further 1% (R0,02 billion) of the expenditure was costs incurred for litigation and claims, while 63% (R1,08 billion) relates to causes such as paying higher than market-related prices to procure personal protective equipment, suffering losses on projects and incurring costs where no value was received. Auditees from national government, Gauteng and the Free State were the main contributors to this expenditure, constituting 92% of the total as follows:

- National government – R1,09 billion (64%)

- Gauteng – R0,38 billion (22%)

- Free State – R0,10 billion (6%)

With the exception of the national Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development, all these auditees have incurred this type of expenditure for the past three years, with some of the main contributors being as follows:

- At the Water Trading Entity, fruitless and wasteful expenditure was attributed to abnormal costs incurred of R0,17 billion and R0,21 billion relating to internal and external projects, respectively.

- At the National Treasury, the main reason for the fruitless and wasteful expenditure was payment for technical support and maintenance on the Integrated Financial Management System programme, which

the department is not using. - At Transnet, the fruitless and wasteful expenditure mainly relates to redundant assets and stock (R0,05 billion) of raw materials that could not be used, theft of laptops and cellphones, damage to motor vehicles, misuse of company assets, employee fraud (R0,05 billion) and poor contract management, including non-adherence to the procurement procedure manual (R0,02 billion).

- At the South African Post Office, the fruitless and wasteful expenditure was mainly interest and penalties on late payments, of which

R0,05 billion relates to the South African Revenue Service. - At the Gauteng Department of Health, the fruitless and wasteful expenditure was due to service providers overcharging on procurement of personal protective equipment.

Despite the limited resources, we still find auditees not diligently and carefully managing funds. This is also apparent from the material irregularities identified, which we cover in more detail in chapter 9. Many auditees also do not follow the required procurement processes to ensure that the best price is paid for goods and services – we provide more details later on in this section.

Performance reporting

Auditees are required to measure their actual service delivery against the performance indicators and targets set for each of their predetermined objectives in their annual performance plan, strategic plan or corporate plan, and to report on this in their performance reports.

Every year, we audit selected material programmes of departments and objectives of public entities to determine whether the information in the performance reports is useful and reliable enough to enable oversight bodies, the public and other users of the reports to assess the auditee’s performance. We select programmes and objectives that align with the auditee’s mandate and, in the audit report, we report findings that are material enough to be brought to the attention of these users.

When an auditee receives material findings on its performance report, this means that it generally struggled to:

- align its performance reports to the predetermined objectives to which it committed in its annual performance plans

- set clear performance indicators and targets to measure its performance against its predetermined objectives

- report reliably on whether it has achieved its performance targets.

Sixty percent of auditees continue to submit poor-quality performance reports for auditing, although some of these auditees corrected all of the material findings we identified. This means that if we had not identified the problems in the reports and allowed the auditees to correct these, only 40% of the performance reports would have passed as useful and reliable, compared to the 72% that ultimately had no material findings. If we had not identified these problems and allowed these corrections to be made, less than half of the auditees would not have had credible performance reports.

Most auditees have inadequate systems to collate and report on their performance information, and officials did not apply the performance management and reporting requirements. The controls to prevent reporting on unreliable information were inadequate and the misstatements remain undetected, even though the performance reports go through various levels of review. Auditors are then put under pressure to identify the matters that need to be corrected as part of the audit process, placing further pressure

on the audit fees.

The poorly prepared performance reports and significant activity to make corrections in response to the audit also raise questions about how credible auditees’ in-year reporting is and how effective their performance monitoring is throughout the year. Poor monitoring and corrective action throughout the year contribute to auditees’ inability to achieve their performance targets or reliably report on their performance. The executive authorities and oversight bodies (such as portfolio committees) also use in-year reporting for monitoring purposes, and without reliable information, their monitoring process is ineffective. It also hinders the accountability processes that those charged with oversight are tasked to implement, including the budget review and recommendations reports that portfolio committees are required to initiate. These reports guide the relevant executive authority in their priorities and associated budget requirements for the following performance period.

Not all auditees could make the required corrections to their performance reports, which resulted in 28% of published performance reports containing significant flaws. The most prevalent material findings on these performance reports (23%) were that the information provided was not reliable. In other words, either we had proof that the achievement as reported was not correct, or we could not find evidence to support it. This means that the achievements reported may not have taken place at all or were fewer than those reported.

Less common (15%) was the indicators and targets used to plan and report on achievement not being useful. This means that what was reported had little relevance to the auditees’ original commitments in their planning documents and anyone attempting to establish whether the commitments were honoured would struggle to get a credible answer from the report.

As with the overall audit outcomes, the sectors lag behind other departments in performance reporting, with only 23% submitting quality performance reports, compared to 38% for other

departments, and only 36% publishing quality performance reports, compared to 76% for other departments. For further details and insight on the challenges of performance reporting in the sectors and the impact on service delivery, refer to chapter 4.

Compliance with legislation

Compliance with legislation

Non-compliance with legislation

Compliance with key legislation improved slightly from the previous year, but remains low, as only 31% of auditees did not have material findings on non-compliance with key legislation. The lapse in oversight and lack of controls relating to compliance were most evident in the areas of:

- the quality of financial statements and the prevention of unauthorised and fruitless and wasteful expenditure (as dealt with earlier)

- procurement and contract management (more commonly known as supply chain management)

- irregular expenditure

- consequence management.

Other notable areas of non-compliance were expenditure management (16%), strategic planning and performance management (12%), and revenue management (8%).

We now look in more detail at two specific areas of non-compliance, namely supply chain management and irregular expenditure.

Supply chain management

In 2020-21, we noted some improvement in the compliance with legislation on supply chain management, building on the improvement trend from the start of the new administration. However, the compliance rate remains low, especially at departments, and the situation is still concerning.

The reasons for improvements were varied, with some auditees making the changes needed for sustainable improvement by enhancing control environments and ensuring stability in supply chain management units or key positions.

At the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities, the accounting officer and senior management were committed to, and directly involved in, ensuring that improvements in internal controls are implemented consistently and in good time. This improvement can be attributed to the additional controls (including preventative controls) management implemented to address the previous period’s misstatements and root causes. Management has also focused on supply chain management issues raised in the previous year and developed an action plan, which included our recommendations to address the previous year’s findings.

At some auditees, however, non-compliance only decreased because fewer tenders were issued, mainly due to budget constraints. For example, the Eastern Cape Department of Education did not issue any tenders for infrastructure projects in 2020-21 due to budget constraints.

It is thus early days to celebrate an improvement in supply chain management compliance, especially given the many procurement failures observed during the height of the pandemic and reported in our special reports. Chapter 5 provides further detail on the covid-19 procurement findings.

We were unable to audit procurement of R2 138 million at 27 auditees (7%) due to missing or incomplete information. The impact of these limitations was as follows:

- There was no evidence that auditees had followed a fair, transparent and competitive process for all awards. If unsuccessful bidders request information on the process, this information would not be available, thus exposing auditees to possible litigation.

- Poor record management created an environment in which it was easy for officials to commit and conceal improper or illegal conduct.

- Due to these limitations, we could not assess whether any part of the R2 138 million might represent irregular expenditure or material irregularities.

The highest contributors to these limitations, accounting for 90%, were:

- Department of Public Works and Roads (NW) – R550 million: The department did not submit any of the tender documents for auditing due to poor record management. The most significant contracts were for upgrading roads (R456 million) and extensions to the Mmabatho Convention Centre (R86,4 million).

- Property Management Trading Entity – R501 million: Due to poor record management, the entity did not submit for auditing the contract and all bid documentation for the unsuccessful bidders relating to the procurement process and contract for the urgent relocation of the national Department of Health from the Civitas building to alternative accommodation.

- Department of Defence – R387 million: The department did not submit one of the procurement contract files for auditing. The file relates to Unified Communication Solution and renewal of Microsoft software licences.

- Roads Agency Limpopo – R378 million: The auditee could not provide the documentation for nine awards as they are currently subject to court litigation by the losing bidder.

- Department of Health (NW) – R107 million:

- The department could not provide the tender documentation for the winning suppliers relating to the contract for the supply and delivery of coal. The reason for the limitations was improper internal controls implemented for the safeguarding of tender documentation.

Although there is no legislation that prohibits auditees from making awards to suppliers in which employees and their close family members have an interest, such awards might create conflicts of interest for employees and/or their close family members. As part of our audit, we assess the financial interests of employees of the auditee as well as their close family members in suppliers to ensure that any conflicts of interest are identified and reported to management, as these may result in an unfair procurement process.

As with employees and close family members, there is no legislation that prohibits making awards to suppliers in which state officials have an interest. However, the amended Public Service Regulations prohibit employees of departments from doing business with the state from 1 August 2016. During our audits, we identified 712 employees who were still doing business with the state (an increase from 560 in the previous year). The onus of complying with these regulations is on the employees, but departments have a responsibility to monitor such compliance.

Despite consistently raising concerns about contracts being awarded to employees and their families, we still find that contracts are awarded without the necessary declarations of interest being made.

The Mpumalanga Department of Health relied on the declarations submitted and the central supplier database compliance reports for all procurement to identify any interests and act in accordance with its policy. However, these reports did not pick up all the interests. This weakness in preventative controls allowed the increased procurement related to covid-19 to contribute to the high number of false declarations by suppliers. The department committed to investigate the false declarations and deal with the root causes.

The KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education relied on the declarations submitted and the central supplier database compliance reports for all procurement to identify any interests and act in accordance with its policy. The department’s internal control and human resource management directorate followed up on the suppliers we flagged to management for investigation of false declarations through our computer-assisted audit techniques. The suppliers were notified that they would have to either deregister as the directors of the company or resign from their employment at the department. Over the years, we have not seen a repeat of previously reported interests.

Uncompetitive and unfair procurement processes are still common. We reported findings (27% of which were material) on uncompetitive and unfair procurement processes at 51% of auditees, and contract management findings (6% of which were material) at 22% of auditees.

Often, findings on non-compliance with supply chain management legislation are viewed and commented on as procedural issues or possible fraud, while the potential losses for government due to the correct processes not being followed are overlooked. Less competition often leads to higher prices being paid for goods and services, while non-compliance relating to contract management can open the state up to losses when contracts are not in place or performance is not monitored. This results in further losses, placing the fiscus under undue pressure.

The aim of the Preferential Procurement Regulations is to support socioeconomic transformation. These regulations have a significant impact on the fair and equitable development of the country’s local economy. The public sector should lead by example to achieve this goal, but we again found that some auditees are failing in this area. As seen in the figure above, 53 auditees (14%) either did not apply the preference point system or applied it incorrectly.

The Preferential Procurement Regulations also require auditees to procure certain commodities from local producers. Auditees also failed in this area, as 77 (44%) of the 176 auditees at which we audited local content failed to comply with the regulation on promoting local producers on awards amounting to R918 million.

There were 38 auditees (10%) that failed to comply with the covid-19 emergency procurement requirements.

Chapter 9 provides further details and examples of what we discovered in terms of uncompetitive and unfair procurement processes and inadequate contract management.

Irregular expenditure

Irregular expenditure is expenditure that was not incurred in the manner prescribed by legislation, and does not necessarily mean that money was wasted or that fraud was committed.

When an auditee incurs irregular expenditure, it indicates non-compliance in the process that management needs to investigate to determine whether it was incurred because of an unintended error, through negligence or with the intention to work against the requirements of legislation (which, for example, require that procurement should be fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and

cost-effective).

These investigations also determine who is responsible for the non-compliance and what the impact is, and provide the basis for determining the next steps. If the non-compliance had no impact and negligence was not proven, one possible step is to condone the expenditure. Alternatively, if negligence was proven, the auditee can take disciplinary action, recover any losses from the implicated officials, or even cancel a contract or report it to the police or to an investigating authority.

Irregular expenditure remains high at R166,85 billion, and auditees are still slow to deal with it.

The biggest increase in irregular expenditure was in national government, mainly as a result of the National Student Financial Aid Scheme increase. If we exclude this amount (R77,49 billion), irregular expenditure for the current year would be R89,36 billion.

For the first time in many years, most of the irregular expenditure (R103,55 billion, or 62%) was caused by non-compliance with legislation that did not relate to supply chain management. As mentioned above, a significant portion of this amount (R77,49 billion) is from the National Student Financial Aid Scheme, mainly due to non-compliance with bursary-related regulations.

The R63,30 billion (38%) that relates to non-compliance with supply chain management legislation can be broken down as follows:

- Procurement without following a competitive bidding or quotation process – R7,43 billion (12%)

- Inadequate contract management – R4,65 billion (7%)

- Non-compliance with other procurement process requirements – R51,22 billion (81%)

All of the top 10 contributors to irregular expenditure are repeat offenders, having previously incurred this type of expenditure within the past three years. Further insight on some of these top 10 contributors is as follows:

- National Student Financial Aid Scheme –

R43,71 billion (56%) of the irregular expenditure was incurred in previous years but was identified and disclosed in the current year. The remainder was incurred in the current year and was mainly due to a failure to consult with respective Ministers on the funding rules and eligibility criteria for the student bursaries. - Transnet – R16,96 billion (55%) of the irregular expenditure was incurred in previous years but was identified and disclosed in the current year. The remainder was incurred in the current year. Some of the more significant matters are being investigated by the Special Investigating Unit.

- Department of Transport (KZN) – R2,05 billion

(32%) of the irregular expenditure was incurred in previous years but was identified and disclosed in the current year. The remainder was incurred in the current year. Non-compliance with other procurement process requirements constituted 87% of the expenditure. The goods or services and key contracts affected included a bus service contract, security services and upgrading of roads. - Department of Roads and Transport (GP) – R2,01 billion (100%) of the irregular expenditure was incurred and identified in the current year – most of this represents irregular expenditure incurred on ongoing multiyear contracts awarded in previous years. All of the expenditure is due to non-compliance with other procurement process requirements and relates mostly to extension of expired bus contracts.

Auditees have a poor track record in dealing with irregular expenditure and ensuring accountability. The year-end balance of irregular expenditure accumulated over many years continues to grow and remains unresolved.

Below are some examples of why this type of expenditure continues to grow.

Approximately R37 billion of the Transnet amount relates to the procurement of 1 064 locomotives that was found to be irregular. These transactions are the subject of ongoing investigations and court processes, the outcome of which will determine the appropriate steps to be implemented for dealing with the irregular expenditure, including recovery of losses incurred (if any), disciplinary steps and/or condonation if there are good grounds to do so.

The Gauteng Department of Health is not investigating all cases of irregular expenditure due to instability in leadership, lack or non-submission of requests for condonement of the irregular expenditure to the relevant authorities, and the fact that most of the irregular expenditure is from legacy issues, such as consignment stock, security contracts and cleaning contracts.

The biggest reason for growing irregular expenditure at the national Department of Defence is

the lack of an effective consequence management and control environment. In the current year,

74 new cases of irregular expenditure were identified, while only three were condoned and none were recovered or written off.

A culture of tolerance and even acceptance of non-compliance fuels the situation where officials are not held accountable and consequence management is not implemented. This blatant disregard brings into question government’s commitment to respect the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, as required by section 41 of the Constitution.

Root causes of unfavourable audit outcomes

Status of internal controls and strength of assurance provided

Over the years, our message has remained consistent – departments and public entities must have a strong control environment with practical, automated and routinely executed internal controls.

Internal controls support the achievement of national and provincial objectives by monitoring the risk of human error, incorrect decisions, fraud, abuse and loss. Such controls also prevent financial loss, wastage and transgressions, and significantly improve financial and performance management and reporting.

Investing in and progressively building a disciplined control culture is the sustainable solution that national and provincial government needs to do more with the limited funds at its disposal. The status of internal controls reflects an improvement over the last three years that correlates with the improvement in audit outcomes – but it is still not where it should be, with almost half of the auditees still not receiving the necessary attention.

Status of internal control

The status of the financial and performance management controls shows that auditees need to invest further in building a disciplined control culture:

- Many auditees still struggle with basic and routine daily transactional disciplines and monthly controls such as reconciliations. These disciplines and controls are also not supported consistently and effectively by information technology system controls.

- We rarely find auditees with good, built-in processes to monitor and review all transactions, procurement, payments and decision-making to ensure that they comply with legislation, best practices and policies.

- There is lack of proper record keeping for financial and performance information, which weakens the potential for credible in-year reporting to enable national and provincial leaders to monitor performance and make well-informed decisions. Consequently, at year-end, financial statements and performance reports are riddled with misstatements.

- Our consistent call to implement audit action plans to address the root causes of audit findings is not getting the required attention, with plans being developed but not executed.

- If sound systems of internal control are lacking, there may be a regression in audit outcomes.

Our reporting and the oversight process reflect on history, as they take place after the financial year. Many other role-players contribute throughout the year to the credibility of financial and performance information and compliance with legislation by ensuring that adequate internal controls are implemented.

We assess the level of assurance provided by role-players in national and provincial government based on the status of auditees’ internal controls. We also assess the impact of the different role-players on these controls.

In chapter 10, we highlight the role of each key role-player in providing assurance.

Since the first year of administration, we have seen a significant improvement in the level of assurance provided by coordinating departments, public accounts committees and portfolio committees.

The poor quality of the financial statements and performance reports submitted for auditing, along with the continuing non-compliance, are clear indicators that there is a need for improved assurance at senior management level.